In 2000, NBC News Meet the Press moderator Andrea Mitchell referred to the ongoing Human Genome Project as a “breakthrough compared to the moon landing and the invention of the wheel.” However, at that time — almost three years before the project would be complete — whether researchers could successfully generate the first human genome sequence was a bit of a gamble.

The Ensembl Project

Before there was GeneSweep, there was the Ensembl Project, an online database to help researchers explore the locations of genes across the immense human genome sequence. Dr. Birney and his colleagues began developing the Ensembl Project in 1999 in anticipation of the completion of the Human Genome Project.

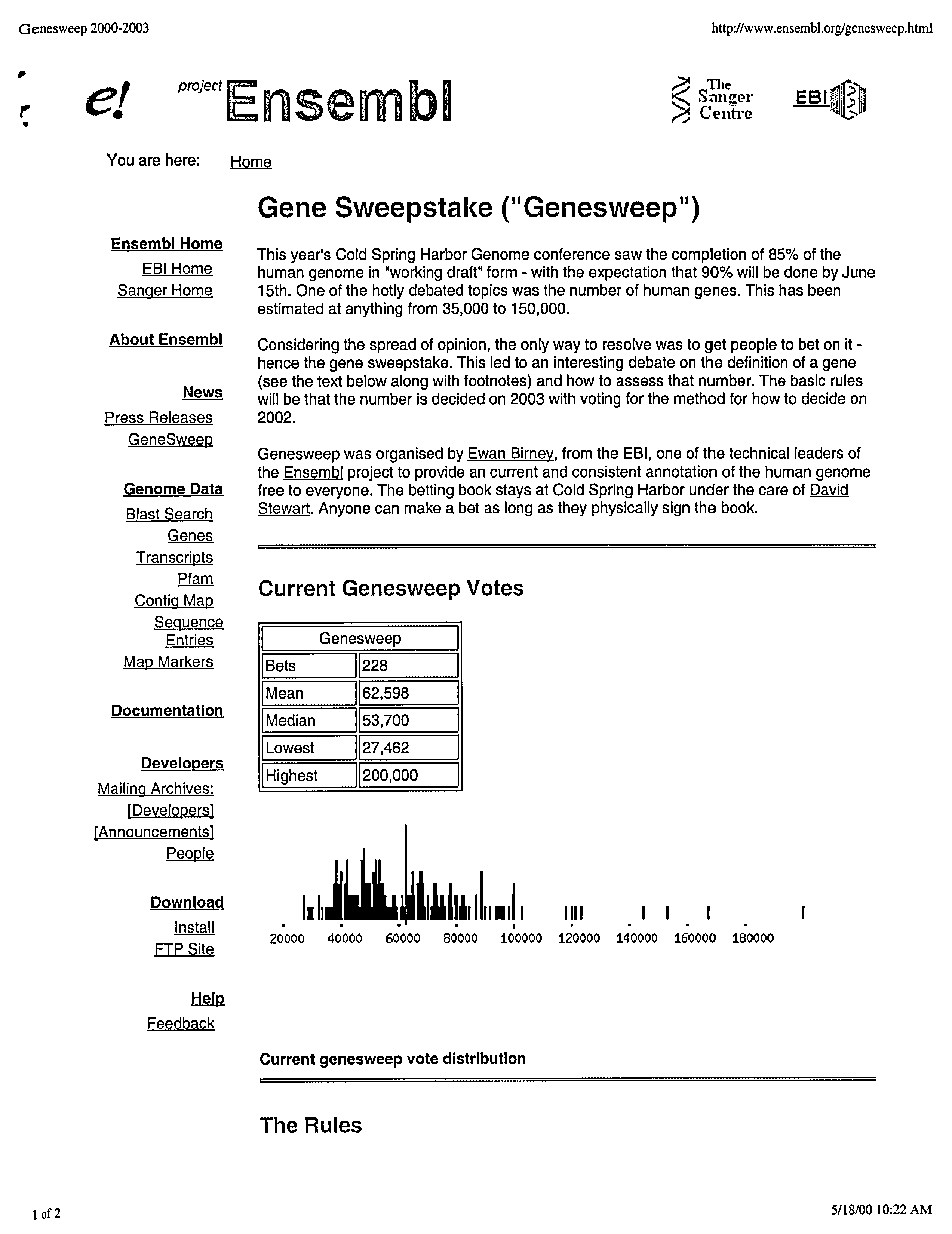

As genes were identified, the Ensembl Project researchers would document the location of these genes in the human genome sequence. This process was increasingly performed in more automated ways using new software tools, which quickly became much more efficient than manual approaches. The Ensembl Project website thus became a key place to get the most up-to-date information about the collection of identified human genomes. It also became a key place to get updates on the GeneSweep vote counts, as shown below.

Caption: An Ensembl Project webpage (on ensembl.org) explaining the origins of GeneSweep, along with a table and bar graph summarizing the bets as of May 2000. (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

Transcript: I was this sort of young, slightly rule breaking — not rule breaking — but anyway very extrovert kid who had seen some of the possibilities of how we could analyze the human genome. I worked very closely with Michelle Clamp and Tim Hubbard to annotate the human genome. So I kind of wanted to get our name out there, get us out there, Ensembl. I did it almost for PR reasons, as well as for fun, as it were. I definitely got a big kick out of going around that evening, that evening, the very first evening. I had a little plastic beer thing, asked people to put the money, and I would talk. There were many Nobel Laureates who bought a number that evening, that day. So it was a great way to meet a whole bunch of people.

2000 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Meeting

Caption: A flyer from the 2000 Cold Spring Harbor Meeting on Genome Sequencing and Biology. (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

At the annual Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Meeting on Genome Sequencing and Biology in May 2000, during which Human Genome Project researchers also announced that they were nearing completion of a “working draft” sequence of the human genome, a French researcher named Hugues Roest-Crollius, Ph.D., gave a talk. He was working for a research center named Genoscope, and his research group had recently sequenced the genome of a small fish called the Tetraodon. A member of the pufferfish family, Tetraodon was studied because it was known to contain a smaller-than-usual genome for a vertebrate species. From the early analyses of the Tetraodon genome sequence, Dr. Roest-Crollius’ group found evidence that the total number of Tetraodon genes might be significantly smaller than what most genome researchers had expected. In a 2024 interview, Dr. Roest-Crollius recounted the events at the 2000 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory meeting.

Transcript: I can’t remember exactly when he raised this old notebook which was going to be the book in which people were going to record the numbers they were thinking about. I think it was like, I think my talk ended the session so it was either mid-morning or end of the morning and he must have been the one next up after the break or after the lunch break. And So by then I was still coming up with the reality of what just happened which is that we had given, I had given this talk and everybody was a bit shaken and every one was completely like discussing the possibility that the number of genes was going to be so low and if so “what was the alternative, you know, how could we explain?” Just all the discussions you could imagine with people realizing that the number of genes was not going to 80,000 but more like 30,000. And so people disbelieving it and people believing it and people, you know… anyway this was all going on and I think that was the most interesting part of it.

The robust discussion generated by Dr. Roest-Crollius’ 2000 talk indeed gave Dr. Birney an idea: Why not have researchers place bets on their predictions for the number of human genes?

Dr. Birney recounted this moment in a 2017 interview for the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Oral History Collection: “I was this young Brit... precocious, doing this, and then I came round with this [betting] book and persuaded effectively everybody in the meeting to put a dollar and put a number in.”

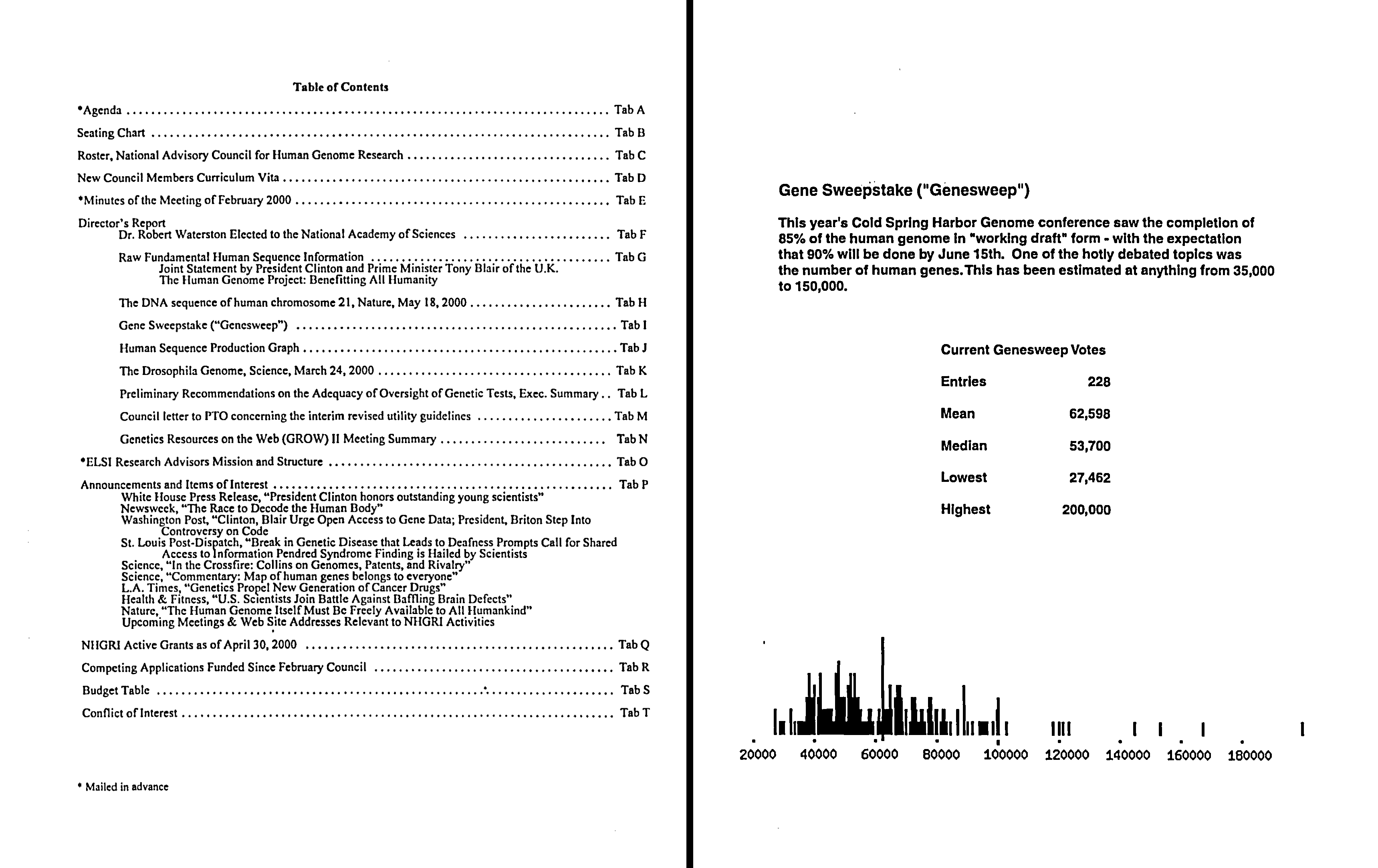

Shortly thereafter, the 29th Meeting of the National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research added further awareness of GeneSweep. Specifically, the director’s report given by the then NHGRI Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D. included a section dedicated to the “Gene Sweepstake,” pointing out that the basis of GeneSweep (i.e., predicting the total number of human genes) was “one of the hotly debated topics” at the meeting.

At that point, the GeneSweep page on the Ensembl website was up and running, with 228 votes already recorded. GeneSweep was off and running!

Caption: Table of Contents for the Director’s Report given at the May 2000 meeting of the National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research (left) and the GeneSweep page document located behind associated Tab I. (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

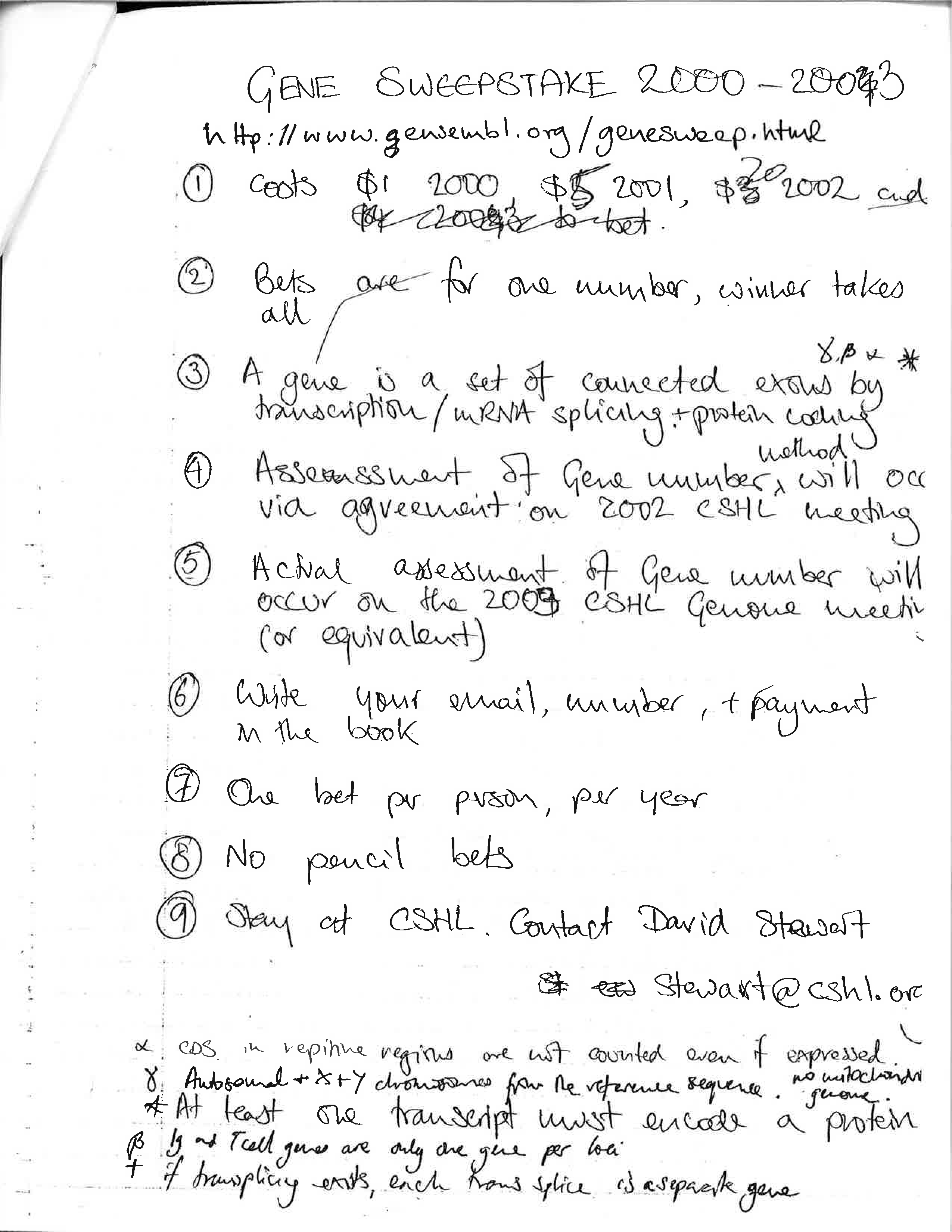

The Rules and “Footnotes”

Every contest needs rules, and GeneSweep was no exception. The rules began as notes that Dr. Birney wrote down in the official GeneSweep betting book, which has since become one of the more well-known historical items from the Human Genome Project. (The book is currently on loan to the LWL – Museum für Naturkunde in Münster, Germany for a temporary exhibition through September 2026). Dr. Birney also posted those same rules on the Ensembl website.

Caption: The rules for GeneSweep, written by Dr. Ewan Birney in the official GeneSweep betting book at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. (Image provided by Dr. Lee Rowen).

The rules dictated the amount of money a person could bet, the limit of one bet per year per person, and the details for how scientists could share their estimation methods. Alongside the rules, Dr. Birney added “footnotes” meant to address the nuances of betting on the total number of something that, in many ways, was scientifically unclear — that is, what exactly is a gene?

At a basic level, a gene is considered to be a region of the genome that codes for a specific protein or a segment of a protein. The resulting proteins, in turn, are used to build cells and tissues that make a human. However, there are many complex steps to create a protein from a gene, and there are also many parts of the genome that are similar to genes but might not exactly fit the simple definition of a gene. So in the early 2000’s, there was debate amongst GeneSweep participants as to what to actually count as a gene.

The footnotes attempted to define at least what GeneSweep would count as a gene, so as to create a level playing field. However, the list of footnotes kept growing.

Dr. Birney later stated, “People would ask me some corner case, and so then, for that corner case, I put a little footnote... There was a lot of footnotes.”

Caption: The GeneSweep footnotes to the official rules, as depicted on the Ensembl Project website in May 2000 (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

“This guy’s mad! There can’t be 27,000”

The actual predictions made during GeneSweep were all over the place. A July 2000 article in the Boston Globe entitled, “Betting on the genes in a human” highlighted this fact, reading, “There is so little scientific certainty today.”

Caption: A Boston Globe article on GeneSweep in July 2000 (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

But why were there such divergent predictions among GeneSweep participants?

When the Human Genome Project began in 1990, the prevailing wisdom was that there were over 100,000 genes in the human genome. That number came up repeatedly and was even mentioned by former NIH Director Bernadine Healy, M.D., in her 1992 testimony given before Congress, saying, “It is estimated, however, that the human genome is made up of well over 100,000 genes.”

Caption: Congressional testimony by Dr. Bernadine Healy, NIH Director in 1992. (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

Read the complete statement from Dr. Healy (PDF)However, by 2000, new data emerged that challenged this number. Dr. Roest-Crollius, whose experience sequencing the Tetraodon genome, hinted that the number would be significantly lower. He ended up predicting 27,000 genes, one of the lowest GeneSweep predictions.

Dr. Roest-Crollius explained how the Tetraodon data informed his thinking at the time in a recent interview:

Transcript: It was completely based on our work. This thing when I went down to the lobby of Cold Spring Harbor downstairs where the book was and I had to put my five dollars down I did not remember exactly the number that we had published in the paper. I knew it was 27,000-something but I didn’t know, or probably 27,700 and something, but I didn’t remember exactly the actual number, the the operation we did, the computational operation we did came up with. So I made it up. And that was truly based — we had two numbers because we had — I don’t know if you read the paper but we had two calibrations, if you like, to divide the number of matches we had the Tetradon and the human genome, which was approximately 100,000 matches, we had two numbers to divide them with. One based on a set of 300 human genes that had been sequenced and was our reference, and the other set was a set of human complimentary DNA, cDNA, sequences that had been sequenced as well. And the two numbers were 2.58 and 3.18, if I remember well. So whether you divide 100,000 by one or the other gives two numbers: one around 27,000 and one around 30-something thousand. So this was our kind of range to say the number of genes in the human genome must be somewhere between those two numbers.

Dr. Birney recounted in a 2024 interview how shocked he was at the time when he saw Hugues’ low prediction, saying, “I remember being in the back of the room [at the 2000 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory meeting] and thinking to myself, ‘This guy’s mad! There can’t be [27,000].’ And to his credit, he stuck to his guns.”

Others relied on different datasets that led them to predicting much higher numbers. Dr. Birney described how analyzing the genome sequence of the C. elegans worm reinforced the belief that the human genome must have a substantially larger number of genes:

Transcript: I think there were a couple of different things that led to people thinking it was a much higher number than the actual number. So the first simple thing is the C. elegans worm, that great progress had been made about C. elegans worm, and it was very clear that it was going to have something like 20,000 protein coding genes. And most people said very simply “a C. elegans worm, a nematode, with 600 — I can’t remember the number — cells, anyway, a very defined, small number of cells. I mean clearly are less complex than a human.” You know, we’ve got to have more, basically, and that was a very simple thought process. We’ve got to have more than a worm!

Geneticist John Quackenbush, Ph.D., of the Institute for Genomic Research, submitted his final prediction of 118,253 genes. He was, however, far from certain about the high number, saying, “It is guaranteed to be absolutely wrong. If I were going to make another bet, I’d make a different one.” Interestingly, both Dr. Quackenbush and Dr. Roest-Crollius published papers about their predictions in the same issue of Nature Genetics. The striking difference in their predictions further emphasized just how little consensus there was about the gene count in the human genome across the genomics community at the time.

Caption: Graph depicting the distribution of total bets made on the final gene count with a range of 20,000 to 200,000 genes.

Who won?

In April 2003, after more than 460 predictions and their associated wagers have been made, the Human Genome Project announced that an “essentially complete” human genome sequence had been generated and that the Human Genome Project had reached its finish line. It was time for Dr. Birney to declare the GeneSweep winners.

Caption: A Science article about the end of GeneSweep in June 2003. (From NHGRI History of Genomics Archive).

Lee Rowen, Ph.D., of the Institute for Systems Biology, had predicted 25,947 genes. This was the closest number to the assessed total of 24,847 genes at the time (later studies lowered this number to ~20,000). In 2024, Dr. Rowen shared her recollections about how she came to her winning prediction:

“I [credit] Jean Weissenbach, with whom we were collaborating on sequencing chromosome 14. He thought that the number of genes was lower than what was being assumed. But...I also thought this independently. Our genome center (Multimegabase Sequencing Center), as suggested by the name, specialized in sequencing long contiguous stretches of the genome. One of the genes on chromosome 14, NRXN3, was HUGE. It took us forever to sequence it, because we had to iteratively keep searching for and mapping BACs [Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes] that overlapped the two ends of the gene, working towards the middle when, eventually, we got the whole gene sequenced. The gene turned out to be ~1.8 mega bases.

This had got me thinking about large genes and I would do these periodic surveys of the UCSC genome browser to scope out how many big genes there were. So...because of this interest, I concluded that the average gene size was bigger than people were thinking and, therefore, that there might be fewer genes in the genome. You could get complexity through alternative splicing. But in year 2000, when the contest was conceived, we had the draft sequence but not all that many long contiguous stretches. So the big gene point was easily missed.” –– Dr. Lee Rowen

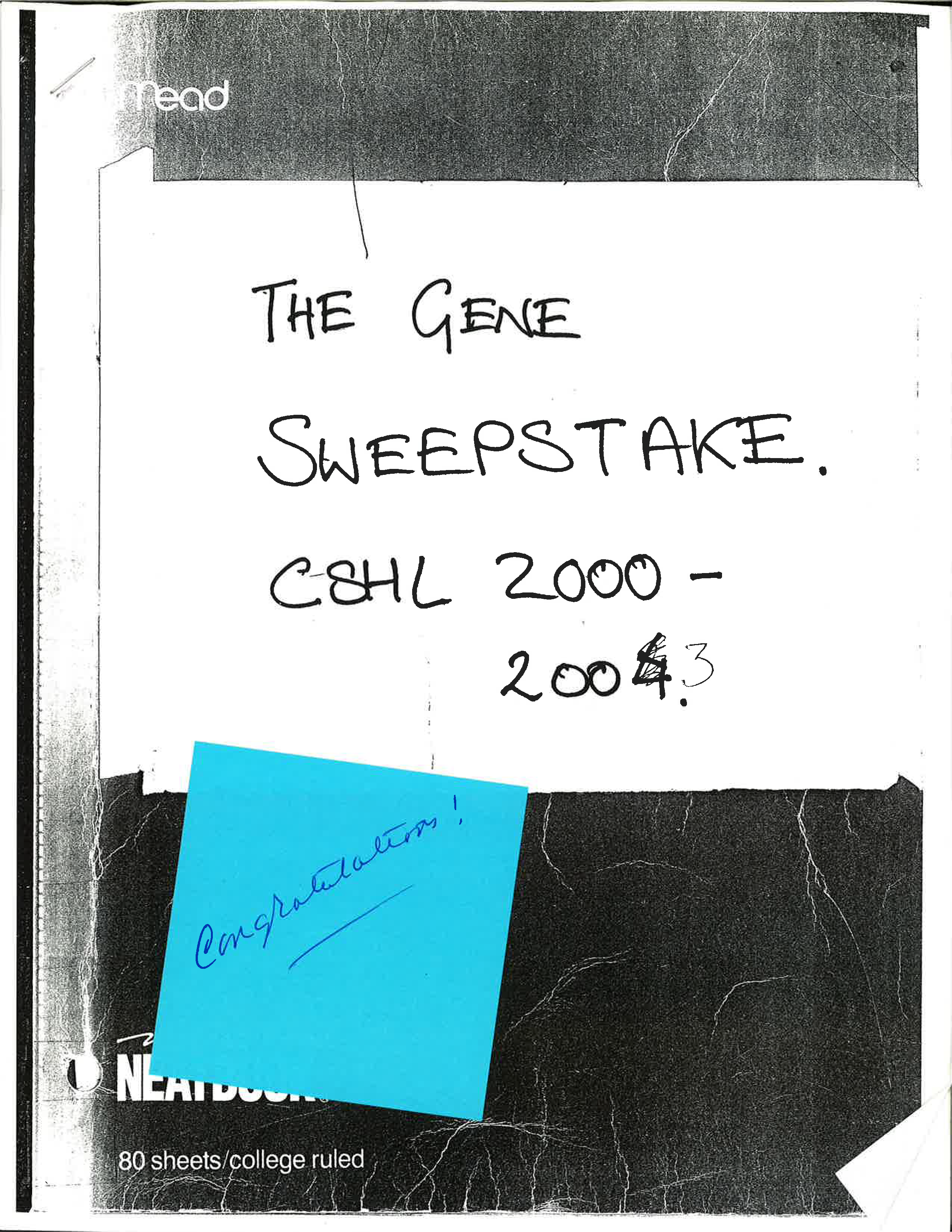

Caption: Cover of the GeneSweep betting book. (Image from Dr. Lee Rowen).

Dr. Rowen received half of the prize money, which totaled $1,200, in addition to an autographed copy of James Watson’s book The Double Helix.

The rest of the prize money was split among two other participants who had predictions close to the final number. Paul Dear, Ph.D., of the U.K. Medical Research Council and Oliver Jaillon, Ph.D., of Genoscope were each awarded a quarter the prize money for their predictions of 27,462 and 26,500, respectively.

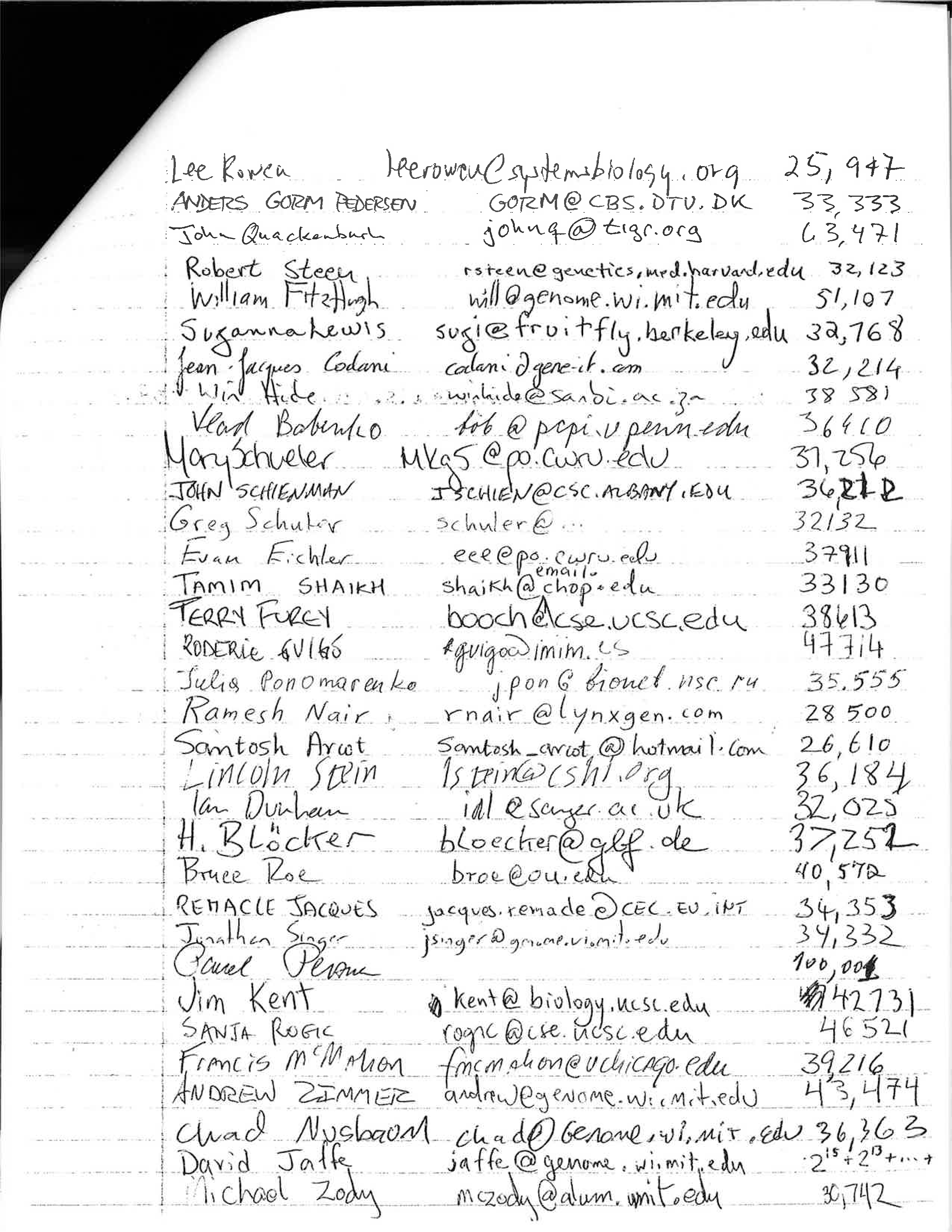

Caption: Page from GeneSweep betting book, with Dr. Rowen’s winning prediction at the top of the page. (Image from Dr. Lee Rowen).

The Legacy of GeneSweep

Science happens in many ways and in various locations. It doesn’t always happen in a laboratory with microscopes and beakers or at a computer. Started at the bar of the well-known Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory during a scientific conference in 2000, GeneSweep is a unique chapter in the story of the Human Genome Project. At the same time, it is emblematic of a central theme of science: humanity’s insatiable desire to know more about ourselves. As Dr. Birney said, “It very human, in fact. So many clever humans got it wrong. It's a very good story.”

Transcript: So, there's two things about this. Firstly, just because a large number of people says, this is the right number, or this is the right thing. It doesn't mean it's right. I mean, that's obvious. I mean, it's many times in, you know, Galileo, you know there's much, much bigger things in the GeneSweep that have shown this, Galileo, or all the way through science Peptic ulcers would be another one where you know that it was thought to be all about acid and stuff like that. Actually, it's a bacterial infection. So, there's lots of these things. Chemiosmotic theory would be another good example where people had to really go against the grain.

But I think actually, that sounds as if scientists are just a bit flaky. And that's actually not the right inference. I think the right inferences is that when scientists don't have data we revert to gossip and speculation, and that's when you go — that's when you just you're not on solid ground. As soon as there's data and you have data and you have ways of thinking about it then you can be data driven, and you can come up with the right. You know much better estimates. And then the estimates sharpen very, very quickly. So, it was fun.

It gets talked about the book, the GeneSweep book, I slightly regret not saying, “Well, that's my book, and I I think we should keep it.” David Stewart here is much cleverer, and he's got it at Cold Spring Harbor — I think they are the official keeper of the book — but it has been exhibited in the Smithsonian and it's been exhibited in some other places. It kind of goes on the tour occasionally, and I think that is because the story is very accessible. Do you know what I mean? People can really understand the story. It’s very human, in fact. So many clever humans got it wrong. It's a very good story. So I like, I do like that. It’s not why I did it. But I do like the feature, you know.

Dr. Roest-Crollius had a different take on GeneSweep’s legacy. In hindsight, he wondered — was it a mistake?

Transcript: Twenty years later now with a bit of hindsight I thought — and I think this was also reflected in the general news at the time — it was a mistake to do that because even though it was fun and it got people really talking more seriously about it perhaps, it also gave the impression, the way it was reported in the general news, that “come on, sequencing the human genome is very expensive. It’s taking money away from other important endeavors like fighting cancer, fighting AIDS at the time. And you are sequencing the human genome at this great cost but you don’t even know what the number of genes is in the human genome, and you’re playing a game to try to bet how much there is? I mean aren’t you scientists? Aren’t you supposed to find out by experiment rather than just by this game?”

So this made us appear a bit as fools, if you like, in the general… I don’t think it lasted very long and I don’t think much was made of it. But I remember the, kind of, ridicule in some news outlets that was associated with this. So in that respect I think it was, perhaps, not a great idea. But it’s easy to say with hindsight.

But anyway at the time, I think, it was fun and yes it was another trick from Ewan but, I mean, he’s like that and I think it was well received. Yea it got more people talking more seriously about it by putting numbers down which I think — people had to think a bit harder about it.

Dr. Lee Rowen also shared her thoughts:

“I think it made a great human-interest story — nerdy scientists do a bet and they all get it wrong! It did probably help to highlight the fascination with the project and its importance — delineating the genes that populate the genomic landscape.”

--Dr. Lee Rowen

Caption: Dr. Lee Rowen (Photo provided to NHGRI by Dr. Lee Rowen.)

Last updated: November 26, 2024